Trend Following During A Time Of Government Intervention

23 November 2008, Financial Times Fund Management

For Charlie Wright and Rob Friedl, managers of the Wisconsin-based Fall River Capital, a commodity trading advisor with $300 million in assets, trend following has led them and their clients to substantial riches. Since its inception in 2000, the firm’s flagship fund has generated annualized returns of 18.66 percent through October, easily topping the S&P 500 by 7.67 percentage points per year.

Despite an awful market, this year has been no different. While the S&P has lost nearly a third of its value, the fund was up 17.47 percent. And this was typical of trend followers in general. BarclayHedge, a data tracking service, found that funds employing this strategy, collectively involving $234 billion, were up 8.9 percent for the year.

“Our success is based not on outsmarting the market,” explains Wright, “but by following it. This way, we can make money in all conditions.” This means that Wright and Friedl are thoroughly indifferent to what fundamentals or their own common sense may otherwise suggest. They don’t care if OPEC is cutting oil production or who Obama selects as Treasury secretary.

Fall River relies on three systematic trading strategies designed around short-, medium-, and longer-term investments. “Buys” and “Sells” of futures contracts–the only vehicle in which the firm invests–ranging across 80 submarkets from fuels to interest rates are determined by pricing models based on 30 years of trading histories.

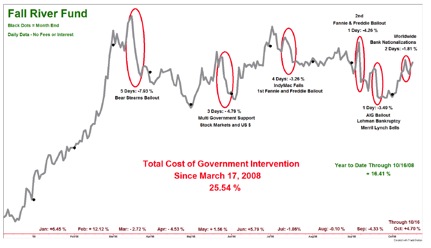

But one reality that Wright and Friedl can’t factor for is government intervention in the market place that goes beyond traditional monetary and fiscal strategy. This started in March with the bailout of Bear Stearns and has continued throughout the year with the salvaging of AIG, Fannie and Freddie Mac, and the country’s major banks.

“These actions were designed to halt and reverse trends,” says Wright, “and the result often stopped us out of our short-term trades.” The reason is related to how Fall River invests. The size of a position is based on the amount of capital the managers are willing to put at risk. The shorter their strategy, the tighter the stops are set. And inversely, their longer trading program has much wider stops, which enables investments to withstand greater volatility without forcing a position to be sold.

Wright found that despite unprecedented government intervention in the US and abroad, which has limited profitability of his short-term Global Opportunities program to 4.25 percent for the year through October, his longer-term Global Strategies program has gained 13.50 percent. The reason: intervention has so far been unable to alter the market’s strong downward bias.

When the Federal Reserve bailed out Bear Stearns in late winter, Wright’s fund, which is comprised of all three programs, declined nearly 8 percent in five days. But six months later, on the day Lehman Brothers was allowed to fail and the Dow lost 500 points, his fund increased 3 percent as bearish trends proceeded unabated. But the fund gave back most of the gain when the government then decided to save AIG.

Over the last six months, which has seen a half of dozen major interventions, Wright has observed that the impact of each succeeding event on his fund has become smaller and shorter in duration. He surmises that this may be due to the market getting accustomed to intervention and his model’s underlying algorithms more efficiently responding to these sudden market shocks.

Despite weathering the turmoil better than most other investors, Wright surmises intervention has cost his fund more than 25 percent.

Glenn Fogle, who manages American Century’s trend following Vista Fund, based in Kansas City with $1.55 billion in assets, was especially challenged not only because the strategy is compromised when markets are turbulent, but because he can only invest long. As a result, the fund has been hit very hard, having lost half its value over the year through mid-November.

The lack of profitable long-only trading patterns is forcing Fogle to try to get ahead of an evolving trend. He believes massive government intervention may be indicative of an inflection point for financials. “Directly or indirectly, it will eventually lead to improvement of the banking environment,” Fogle says, “thus likely to reverse the industry’s downward spiral.”

Accordingly, he’s increasing his financial exposure from 1.55 percent at the end of August [well under his Russell Mid-Cap Growth Index benchmark weighting of 6.3 percent] to nearly 9 percent as of the end of October [well ahead of his benchmark by 2.26 percent]. Over the past 6 weeks through mid-November, this has helped his sector exposure to outperform the Russell index by nearly 3.7 percent.

Being able to bet against the market has enabled hedge fund manager James Melcher, who runs the $785 million New York-based Balestra Capital Partners Fund, to more successfully profit from getting ahead of a trend. He did this most successfully by investing in credit default swaps of mortgage-backed securities and investment bank bonds starting in 2006 when these securities were still rallying. This helped the fund soar nearly 200 percent in 2007 and nearly 24 percent through the first three quarters of this year.

Because government intervention has come late in the crisis, only the tail end of Melcher’s trades were affected. “Intervention has so far provided only brief relief,” observes Melcher, “and subsequent action has had decreasing impact.” He fears worse is to come.

“Government intervention is indicative of the failure of monetary policy to stabilize the markets,” observes Bryan Sadoff, comanager of the trend following Sadoff Investments, a fee-based manager with $400 million under management based in Milwaukee. He notes the only two times in history when cutting rates didn’t restart the economy was in 2002, after the Tech bubble burst, and during the Great Depression.

Sadoff believes this isn’t a time to be buying securities. Over the year he has pushed up his cash position from 15 to 65 percent. Moreover, he thinks that additional government intervention would be a sign that recovery is still some distance away and that substantial risks remain in the market.

GIR's Investing in the New Europe

GIR's Investing in the New Europe